RIP Patricia Kennealy-Morrison, Who Refused To Be Only a Footnote

Among the many things she tackled in a productive life, Patricia Kennealy-Morrison kept a running focus on two deceptively tough ones.

The first was convincing rock fans, and the world in general, to take a less mythic view of Jim Morrison, the late lead singer of the Doors and her one-time love interest.

The second was convincing the world to see her as more than a footnote in the Jim Morrison story.

That’s a hurdle for anyone, especially women, who have ever been romantically associated with entertainment celebrities, because it almost automatically becomes the first line of your obituary. Kennealy-Morrison, who died July 23, knew it, and maybe that was one motivation behind how hard she worked over her 75 years to leave her stamp on more.

As a music magazine editor, she helped pioneer serious rock journalism. She wrote a series of Keltiad fantasy novels. She wrote a series of bemused rock-related murder mysteries. She wrote a book on Morrison. She started her own publishing house, Lizard Queen.

Google “Patricia Kennealy-Morrison” and you don’t just get “Once dated Jim Morrison.”

Her quest was made more complicated and more interesting, though, because she never renounced or downplayed the Morrison year in her life.

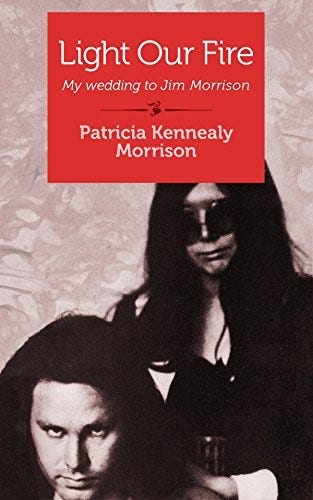

On the contrary, in 1979 she added his name as a hyphen on her own. Her reasoning: In 1970, a year before his death, they had joined in a hand-fasting ceremony, a Celtic Pagan version of a wedding. “It was,” she correctly noted, “the only wedding ceremony in which he participated.”

She referred to him as her husband, though they split up later in 1970. At the time of his death, in a Paris bathtub at the age of 27, his female partner was Pamela Courson.

This has led some to paint Kennealy-Morrison as your basic scorned woman, rewriting history into how she wanted it to have happened.

Not so, she repeatedly said. She was writing the part of Jim Morrison history that she knew.

“It’s the Rashomon thing,” she said a couple of years later. “You could have 14 people who knew Jim and you’d get 14 perspectives. But I think mine was closer than most, and even if you don’t completely buy it, I think you should hear it.”

At the very least, she was not a Suze Rotolo, who spent much of her life waving off people who wanted to talk about Rotolo’s early relationship with Bob Dylan. Kennealy-Morrison never brushed aside a Jim discussion, praising anyone she felt got it right and scorching those she felt got it wrong.

The latter group at times included other members of the Doors, notably keyboardist Ray Manzarek. She thought the biography by Doors hanger-on and finally manager Danny Sugarman, No One Here Gets Out Alive, was barely worth trashing.

She trained much of her fire on filmmaker Oliver Stone, whose 1990 movie The Doors made her so angry that she said her own Morrison book Strange Days, written two years later, was motivated largely by a desire to catalog the ways Stone got it wrong.

“Oliver went for what he understood,” she said in a 1992 interview. “He never knew or saw Jim. So he invented stories when the real-life story was so much more interesting.

“The Doors are portrayed as sullen idiots — and where’s the guy who wrote all those songs? Jim asking ‘What rhymes with fire?’ Using a rhyming dictionary? The distortions are what bother me the most.”

Not surprisingly, she hated the brief portrayal of her own character, noting that for starters Stone called the hand-fasting ceremony Wiccan when it was really Celtic Pagan.

Yet for all that, she said, “I still think my character came off better than the other women in the film. At least she had attitude, even if Stone trashed it.”

Courson was portrayed more sympathetically, which Kennealy-Morrison called another insult to the truth.

“She was painted as Saint Pamela of Santa Monica,” Keannealy-Morrison said. “They tried to prevent her being portrayed as the drug addict she was. Her addiction killed Jim. She fed him heroin, then wandered out to nod off.”

The Stone movie, she said, became a prominent element in a general drift over the years toward turning Morrison into a myth — the dark, brilliant, tortured, elusive, charismatic, tragic rock genius imprisoned by fame. Think Kurt Cobain or Amy Winehouse.

“When Jim was being the rock star, I’d watch him give five completely different interviews to five writers,” said Kennealy-Morrison. “He’d figure out what they wanted and tailor his comments to that person. He was very perceptive, and he also wanted people to like him. I really think he had low self-esteem.

“But the rock star wasn’t the Jim I knew. The Jim I knew was very much a regular person. That’s one reason we got along, because with me he could be normal. So it was different with me, and I think I got the best of him.

“But people who only know the myth prefer the persona to the person.”

Kennealy-Morrison stayed on the Morrison case over the years. She was exasperated when his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction was accepted by a sister “with whom he hadn’t spoken for the last seven years of his life.” She was angry when Manzarek launched a Doors reunion tour,” saying drummer John Densmore got it right when he said there could be no Doors without Jim.

In fact, she noted, the Doors had broken up before Morrison died. “That was the right decision,” she said. “They had taken it as far as they could.”

She suggested Morrison needed to get out of the rock world altogether, maybe get into some other creative area like film, to save his life.

“You have to remember how young we were when all this was happening,” she said. “We were babies, children. Like with the drugs. People hear ‘drugs’ and think oh, they must have been addicts. No. Back then, for a lot of us, drugs were fun. We had great times with drugs. The trouble is there was less awareness of when you went too far. There was no Betty Ford Clinic.

“I think if Jim had made it to 30, he would have survived. In your late 20s, 28 or 29, things start to come together. You grow up. You’ve gotten enough of the puzzle. I think Jim was beginning to see that.”

That did not mean Kennealy-Morrison thinks she and Jim could ever have lived the 1950s American dream.

“The white picket fence, kids, that wasn’t us,” she said. “We were two creative people, which is a big reason it couldn’t have and didn’t work between us.”

Kennealy-Morrison’s time as a rock journalist turned out to be only a short part of her life, when she wrote for and ended up editing Jazz & Pop magazine from 1968 to 1971.

One of the few women writers to break into what was generally seen as the macho domain of guys, she was among the first wave who treated rock ’n’ roll as a serious art form, championing bands like the Doors and her other favorite, Jefferson Airplane.

She was also among the early writers to get tired of much of what she was hearing. Toward the end of her Jazz & Pop years in the early 1970s, she wrote an essay decrying what she saw as a tsunami of hollow lyrics and endless pointless guitar solos.

Two decades later, she hadn’t changed her mind.

“REM is the only band I really like now,” she said. “A verse and a hook. Sarah McLachlan is good. But even a lot of the stuff from the ’60s sounds dated to me now. The Byrds, Dylan. It feels like period pieces and doesn’t have all that much to say.

“Springsteen is a mechanic who happens to play guitar. It does nothing for me. To me, uniqueness is what counts. The music has to engage you, it has to go a step beyond, it has to engage you intellectually.”

When much of the music no longer did that for her, she moved on. She thinks Morrison would have done the same.

Had he done so, he would doubtless have spent his life walking a tightrope between his Doors legacy and whatever he did that wasn’t the Doors.

He died before that became an issue, but Kennealy-Morrison stuck around to walk that line, keeping a residence in a world by which she did not want to be defined.