Don Imus Leaves a Trail of Way More Than Dust

This is the last cowboy song

The end of a hundred-year waltz

Voices sound sad as they’re singing along

Another piece of America lost

— Ed Bruce, “The Last Cowboy Song”

The impending semi-retirement of Don Imus doesn’t mark the end of personality radio. It just removes one of its most important and best practitioners.

Imus in the Morning, the show Imus has hosted for more than four decades, packs up its saddle on March 29.

The 77-year-old Imus says he ain’t quittin’, he’s just movin’ on, because his bosses at the bankrupt Cumulus can’t afford him any more.

Whatever the reason, he won’t be on the radio every morning, in various proportions being cranky and smart and contrary and funny.

His impending departure has sparked a round of valedictories, some from people who appreciate what he’s done, some from people who don’t and some from people who only half-know the show and thus find it easy to define his career by the morning in 2007 when he ill-advisedly referred to Rutgers women’s basketball players as “nappy-headed ho’s.”

That was thoughtless and ugly, as Imus acknowledged too late to save his jobs at WFAN and MSNBC. The Rutgers incident subsequently has also made it easy for those who don’t like him to write him off as one more “shock jock.”

There are reasons to like Imus or not to like Imus. But to dismiss him as just a “shock jock” proves only that the speaker never spent much time listening to him.

Those who did — particularly from about the beginning of the first Bush administration to about the end of the second — heard something far different.

They heard radio for grownups, a fast-paced stream of commentary on politics, culture, sports, music and life that was reliably entertaining and at times downright enlightening.

He had the deceptively rare skill of being able to snap off what sounded like a nasty insult and get away with it because, on some confessional level, his listeners had had the same thought — or just realized that while the remark was tasteless, it was funny.

Sometimes he would follow it with a more balanced assessment of his subject, and on some odd psychological level, that was reassuring. It told us we too could have a snarky thought, however unspoken, and still make a mature adult judgment.

Imus occasionally had to do some tightrope walking. He had guests whose stipulation for an appearance was a buffer zone, before and after, devoid of juvenile insults.

But during his peak years, he had an A-list of guests from across the ideological spectrum in the political, cultural, academic, music and media worlds. Bill Clinton was an Imus guest, though a borderline Imus joke at the 1996 Radio & TV Correspondents dinner about Clinton’s reputation with the ladies drove a stake through that relationship and preceded years when Imus routinely trashed Hillary Clinton.

Imus didn’t need Clinton. His regular guest lineup included presidential candidates John Kerry and John McCain, alongside the likes of Tom Brokaw, Tim Russert, Frank Rich, Anna Quindlen, James Carville, Mike Barnicle, Mike Lupica, Paul Begala, Jeff Greenfield, Alfonse D’Amato, Dan Rather, Chris Dodd, Dick Gregory, Doris Kearns Goodwin and Michael Beschloss.

One reason he acquired that roster was asking smart and informed questions, which he formulated with his long-time sidekick Charles McCord, and giving them time to answer.

The occasional bad-boy question was asked with appropriate discretion and guests, like staff, were encouraged to tweak Imus in return. His 1994 marriage to Deidre Coleman, 23 years younger, provided years of insinuation.

Imus’s explanation for his insults was simple and could be roughly paraphrased as “We’re a radio show, we make fun of everybody, get over it.”

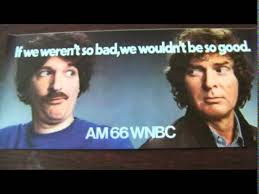

When WNBC morphed into WFAN, becoming America’s first all-sports radio station, it kept Imus in the Morning in hopes he would lure listeners to a format that almost nobody in the radio biz thought would work.

At the end of Imus’s WFAN shift every day, he played this taped message: “This concludes the entertainment portion of the WFAN broadcasting day. WFAN now presents the rest of its programming schedule, 86½ hours of imbecilic prattle between contemptibly limited provincial program hosts talking on the telephone to a band of 13 equally insignificant housebound agoraphobes with sports obsessions.”

He later taped a similar message for stations that carried his show in syndication, suggesting that the rest of their programming days were an incoherent mish-mash of loser hosts whose incompetence compelled the station to subscribe to Imus’s show in the first place.

It was so bizarre it could only be a joke and if here and there it might be a little bit true, that made it funnier.

Still, hosts who live by the insult can be fired by the insult. The late host Bob Grant, after being fired himself, declared it humanly impossible to talk on the radio for 15–20 hours a week and not at some point say something you wish you’d phrased differently, or not said at all. Imus dodged a number of those bullets over the years before he didn’t dodge Rutgers.

More to the point, insults were never the heart of the Imus show. It was about conversation. Imus and his team were people you’d love to have sitting across your kitchen table or riding along in your car, just so you could listen to them talk.

You’ve also just defined good radio.

Imus was the ringmaster of his conversation, and as Allan Sniffen of the New York Radio Message Board noted this week, he set a gold standard for pacing a radio show. Whether it was from his early days listening to music jocks like Wolfman Jack and Robert W. Morgan or just pure instinct, Imus knew when to cut a bit and when to extend it, when to keep listening and when to break in. His infamous obsession with Alger Hiss notwithstanding, he understood what would keep his listener engaged.

He also understood teamwork, and how people who work together become synched.

That started with McCord, his long-time sidekick, who started as the show’s newsman and became a primary writer and partner in ideas. McCord was well-informed, quick-witted, marvelously efficient with words and untimidated by his cranky boss.

Also chiming in regularly were engineer Lou Ruffino and producer Bernard McGuirk, who will team up with Sid Rosenberg to take Imus’s morning slot on WABC (770 AM) in New York. It was Imus’s late brother Fred who, after hearing McGuirk’s casual banter some years ago, suggested Don open his mic. Good call.

For various stretches the Imus team has also included long-timer Rob Bartlett, Tony Powell, Connell McShane, Larry Kenney and sports guys from Mike Breen to Warner Wolf. It probably should be noted that doing sportscasts on Imus’s show has often seemed like sitting at a bar trying to hold a conversation while the guy on the next stool — in this case, that would be Imus — keeps poking you in the ribs.

And speaking of interrupting a conversation, I should break in here to confess that in my own first up-close encounter with Imus, I walked out on him.

It was the end of January 1975 and Imus, a hit on New York radio, was doing a three-night standup comedy run at the Bottom Line in New York’s Greenwich Village.

His opening act was Kinky Friedman. My good friend Ron and I were both Kinky fans, so Helene, Ron, Marge and I decided to go to the show.

The late lamented Bottom Line was a wonderful club with very compact seating. The waitresses who had to navigate the place slithered around the tables and chairs like cobras serving a snake charmer.

The half dozen front tables were perpendicular to the shallow stage and pushed right up against it. We arrived early and for whatever reason were seated at the front center table. We could have reached out and touched Kinky’s boots.

Anyhow, Kinky put on a fine show, and when he finished we debated what to do next. On the one hand, we all knew Imus from the radio. Loved his Billie Sol Hargis bits, knew several verses of “Plastic Jesus.” On the other, we had to drive back to New Jersey and get to work the next day. For lack of a decision, we were still seated when Imus came out and sat down on the stool, four feet in front of us.

I can’t reconstruct his act, except that it seemed to consist almost entirely of profanities. We listened a little while, looked at each other, acknowledged we weren’t laughing and decided to leave.

In retrospect, we could have handled it differently. We were young and we didn’t.

It took Imus very little time, as I recall, to redirect his profanities toward these four people who were walking out in the middle of his act.

Furthermore, since the Bottom Line essentially had no aisles, walking out was not an efficient process. It took a while, during which Imus did more improv on rude patrons.

When we got outside, it suddenly seemed very quiet.

Even aside from this Bottom Line snub, the ’70s were a roller coaster for Imus. He came to New York, became a sensation, took a lot of drugs, got exiled to Cleveland and came back to New York.

A few years later he started growing his show up. While it had never just been about ordering 1,200 hamburgers or asking callers if they were naked, those kinds of bits had defined the show — and while that had made him a lot of money, he realized he was now interested in different things and a different kind of show.

By the time he launched on WFAN in 1988, he was starting to make the show into morning radio for someone more like himself — someone who still liked the music and the radio he grew up with, but also wanted to talk about things you talk about when you’re not a teenager any more. Corrupt politicians. Waylon Jennings. For the next 30 years, he did.

Over those years Imus racked up dozens of awards and honors. Time named him one of the 25 most influential people in America. He’s in every Hall of Fame.

As his radio persona would suggest, he’s never been “Aw, shucks” about any of that. When Anthony Mason interviewed him on CBS Sunday Morning last weekend, he rated himself one of the top five radio personalities of all time. Not modest, just true.

He’s bragged less about his charity work, which includes raising millions for causes like pediatric care. For years he ran the Imus Ranch for kids with cancer, saddling up and riding alongside them every summer.

Imus was never for everyone. Over the years, there have been plenty of people who walked out on him, literally or figuratively, and never returned. Since 2011, when McCord left in April and Fred Imus died in August, the show has gradually undergone a downshift.

But that’s not Don Imus’s radio legacy. His legacy is almost 50 years of a radio show that, for all its insults, always respected the millions of people on the other side of the microphone.